MODELING GRAVITY WAVES IN AN ALUMINIUM REDUCTION CELL

WITH OPENFOAM

Marc Dupuis, Jonquière

Michaël Pagé, St-Nazaire

In recent years extensive modeling work has been done to assess if the usage of an irregular cathode

surface modifies the MHD stability of an aluminium reduction cell. Two types of studies have been carried

out: full 3D steady-state analysis and shallow layer 2D transient analysis. Neither type of analysis is well

suited to examine the effect of an irregular cathode surface on the cell stability.

The present work proposes a new method to analyse this stability problem. Lateral gravity waves were

simulated in a 3D lateral slice of an aluminium reduction cell. The model was solved by using the VOF

formulation of the OpenFOAM code. Results of the evolution of the bath-metal interface are presented for

a reduction cell having different types of irregular surfaces. That evolution is compared to the flat cathode

surface case; irregular surfaces provided little extra damping of the gravity waves.

Introduction

The irregular cathode surface technology is under continual development in China [1]. A recent Chinese

paper outlined a detailed 3D model based on ANSYS and CFX solvers [2]. Steady-state solutions were

presented for a reduction cell with either a flat or an irregular cathode surface. Both MHD and gas release

under the anodes were driving the fluid motion. The steady-state results of the 3D model with irregular

cathode surface clearly demonstrated, that the bath and metal flows were three-dimensional in nature (see

Figure 12b of [2]).

Studies using a 2D transient model (MHD-Valdis) with bath and metal flows in two horizontal shallow

layers could not identify any significant impact of an irregular cathode surface on the cell stability [3, 4, 5,

6]. This suggests that either using irregular cathode surface do not affect cell stability or that it is the three

dimensional flows introduced by irregular cathode surface and not taken into account by MHD-Valdis that

affects the cell stability. Despite that limitation, MHD-Valdis remains an efficient stability analysis tool for

standard cells with a flat cathode surface where the flows are essentially two dimensional in nature.

Since the bath-metal interface motion is a time dependant phenomenon, a cell stability analysis should be

based on a transient model. The above remarks indicate that in the case of irregular cathode surface, the

model should also be in 3D since this type of cathode surface generates three-dimensional flows.

A new modeling approach

The variable Lorentz forces in the metal pad of a reduction cell drive the fluid movements and the viscous

damping reduces the fluid movements [7, 8]. The aim of an irregular cathode surface would be to increase

the viscous damping in the metal and thereby to enhance cell stability.

For a bath-metal interface to move around the cell, both the molten metal and the bath must be displaced.

Since the bath layer thickness under the anodes is much less than the metal pad thickness, the speed of the

bath flow has to be greater than the speed of the metal pad flow. Hence viscous damping in the bath is very

important to the bath-metal interface wave dynamic and must also be considered.

In view of the limitations of the models presently used for stability analysis of reduction cells with irregular

cathodes surfaces, a new modeling approach was developed and tested. The new approach used a transient

3D model consisting of a lateral slice through a reduction cell. The bath and molten metal were subjected to

lateral gravity waves by initially inclining the bath-metal interface. The cathode surface was either flat or

with different versions of irregularities. The speeds of the bath and metal layers and the movement of the

bath-metal interface were calculated over time.

Selection of a proper numerical code to simulate a free interface wave

Only a few codes are able to cope with the physic of the proposed model, which is a transient 3D multi-

phase flow problem; the open source code OpenFOAM is one of them. OpenFOAM has become a popular

code in many applications due to its free surface modeling capabilities [9], which are comparable to other

VOF solvers like CFX [10].

The motion of the free interface between two immiscible liquids in a closed rectangular container has been

studied experimentally in a physical model. Figure 16 of [11] shows the gravity driven interface motion

between two liquids in a closed container. However, such measurements are difficult to reproduce

accurately [12]. This type of free surface wave was successfully modeled by using the OpenFOAM code

[13]. Flows around obstacles like those added to the cathode surface have also been modeled successfully

by using the OpenFOAM code [14].

A similarity between these above described problems successfully solved by OpenFOAM and the gravity

driven bath-metal interface wave in a reduction cell problem suggests that the use of OpenFOAM code is

appropriate for solving the proposed lateral slice model.

Setup and solution of the lateral slice model

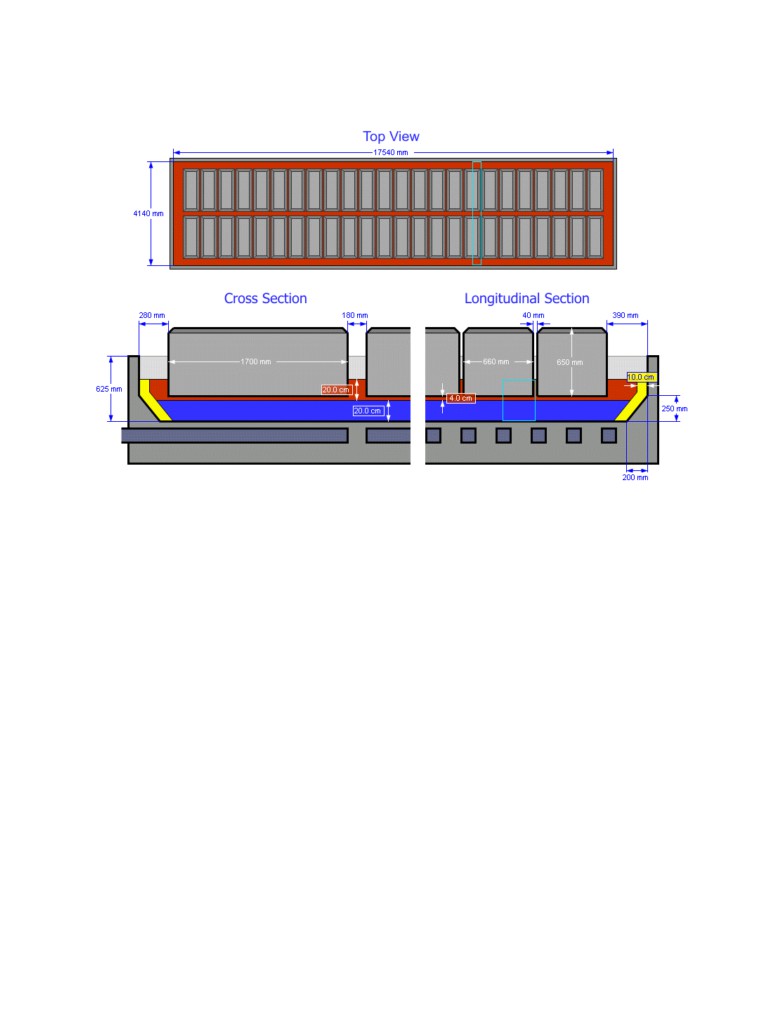

The lateral slice model geometry is based on the cross-section of the GY420 cell design [15]. Different

views of the cell design are shown in Figure 1, which was produced from the Peter Entner CellVolt

application [16]. A fairly standard bath composition was selected for this study (see Figure 4 of [17]).

The model depth (300 mm) extended from the front frictionless symmetry plane located at half the anode

width to the back frictionless symmetry plane located at half the anode width between two adjacent anodes.

The length (3940 mm) of the slice model was typical of a cell cavity width of a GY420 cell less a 100 mm

uniform ledge thickness at both sides. The height of the slice model was composed of three layers: 200 mm

for the metal pad (for the flat cathode surface case), 200 mm for the bath layer and 75 mm for the air layer

on top. The anode-cathode distance (ACD) was 40 mm. The cathode surface was either flat or with

different types of irregularities. Figure 1 of [17] is showing the geometry of the flat cathode surface case

while Figure 10 of [17] is showing the geometry of the first type of cathode surface irregularity studied

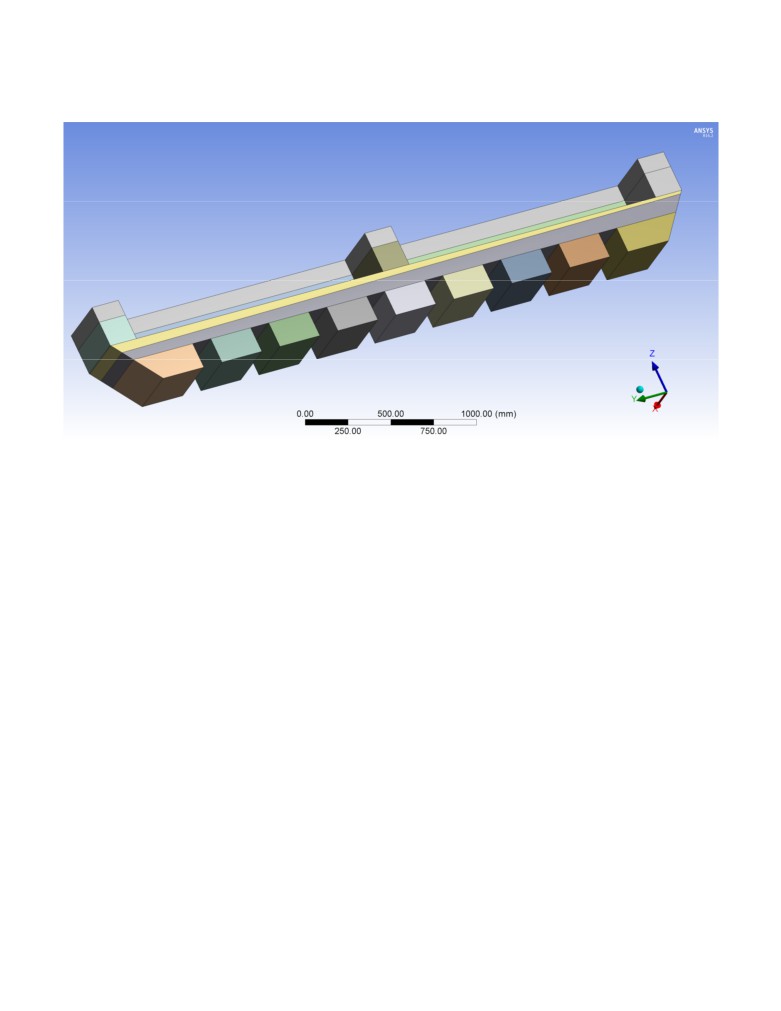

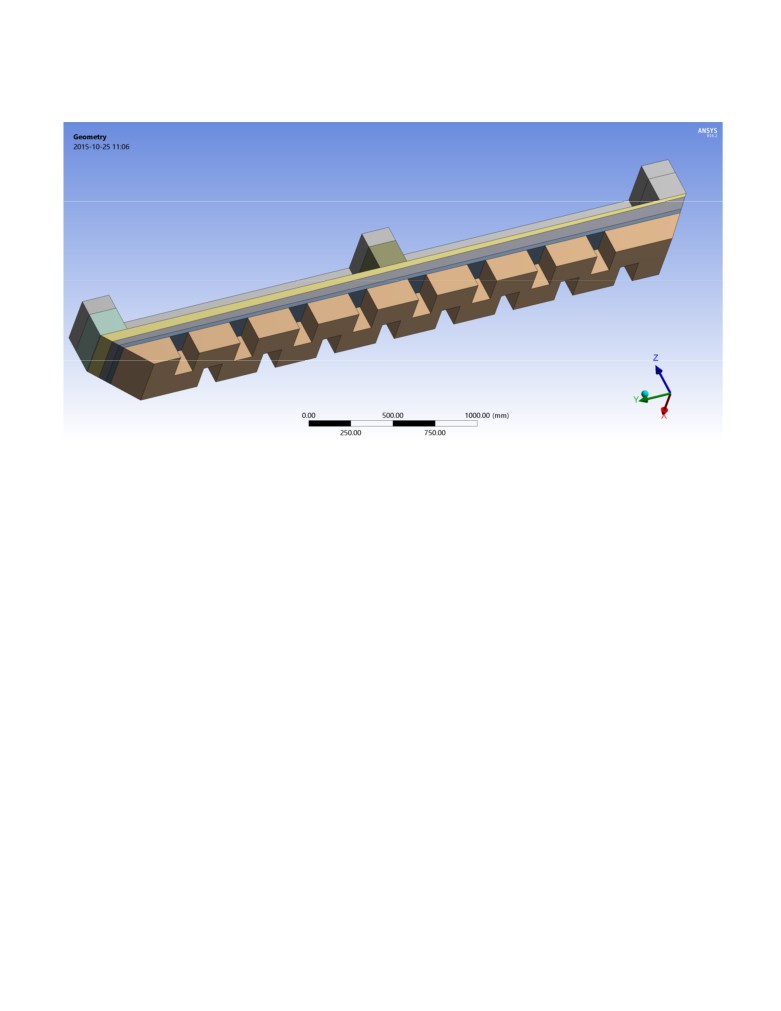

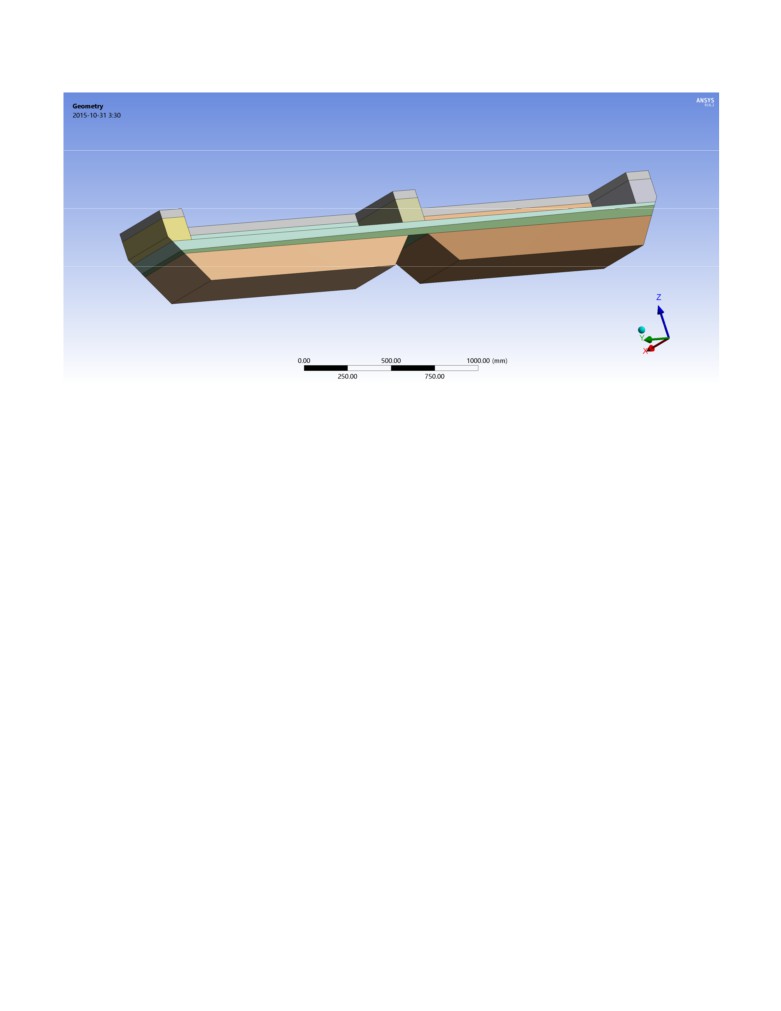

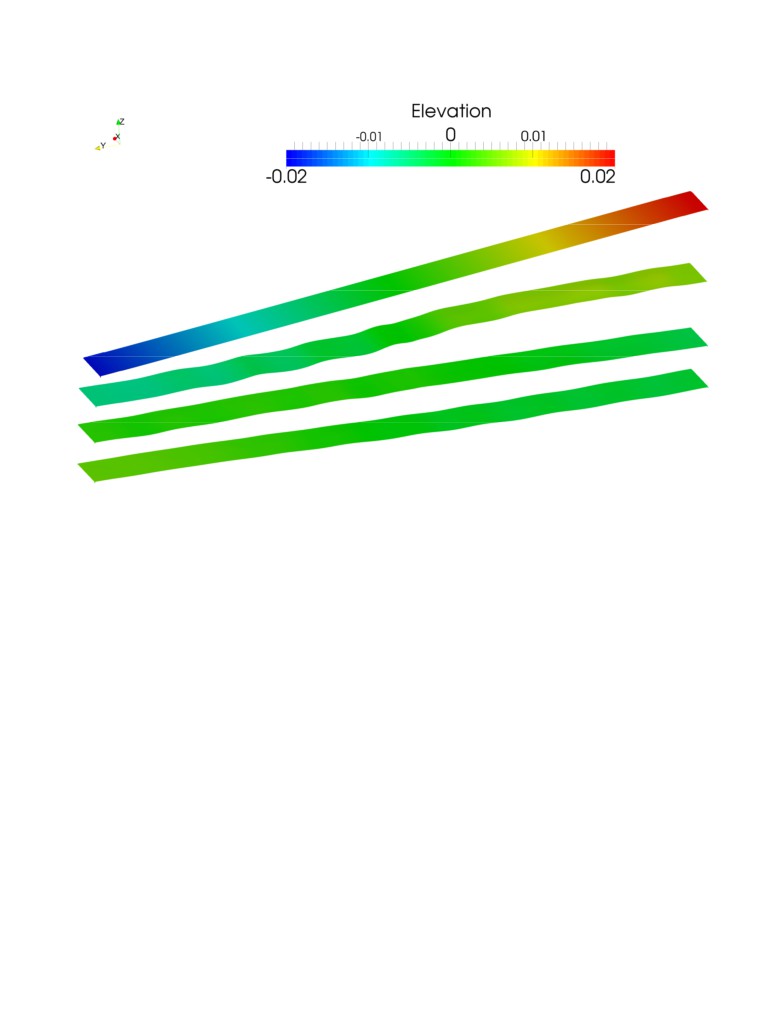

being 8 continuous longitudinal ridges 100 mm high and 200 mm wide. Figures 2 to 4 are presenting the

geometry of three new types of cathode surface irregularities studied next, namely

8 continuous

longitudinal ridges 160 mm high and 125 mm wide, 16 discontinuous and alternating longitudinal ridges

160 mm high and 125 mm wide and a single trapezoidal continuous longitudinal ridge located under the

center channel leaving only 4 cm of metal pad thickness under that channel. In all the cases studies, the

metal pad volume remained unchanged.

The mesh of the different lateral slice model versions consisted of about 1 175 000 hexagonal finite

volumes of fairly uniform size with an orthogonal quality of around 0.77 (see Figures 3 and 11 of [17]).

The mesh density was somewhat coarser than the one used in a wind engineering study [14]. However, it

was fine enough to resolve the boundary layer at the solid surfaces (cathode, anode and ledge) fairly well.

The mesh was perfectly aligned with the initial position of the bath-metal interface in order to ensure a

smooth start of the transient solution.

The transient solution was started with a sloped bath-metal interface of -20 mm on the left side and +20

mm on the right side of the lateral slice model. The motion of the fluids was calculated using an explicit

solver available in the OpenFOAM 2.3.0 code [18]. The multiphase Euler solver was used with a

maximum Courant Number of 0.05 and maximum time step of 0.02 seconds. Because of its demonstrated

ability to predict viscous drag fairly well, the k-ω SST (shear stress transport) turbulence model was used in

the flow calculation [19]. Continuity of the velocity was assumed at the bath-metal interface.

The transient calculations were made for a total of 60 seconds, which allowed about three oscillations of

the bath-metal interface. The calculations were performed on a DELL Xeon ES-2697 V3 computer having

128 GB of RAM and 28 cores. The computer took about 30 CPU hours to calculate that transient solution

using all 28 cores.

Solution of the “reference” flat cathode surface model

The solution of the “reference” flat cathode surface model is presented in Figures 6 to 9 of [17]. The

positions of the bath-metal interface are shown at intervals of 15 seconds in Figure 6 of [17]. Figure 7 of

[17] shows the velocity field at the front symmetry plane, which passed through the anode center, after 15

seconds. The maximum bath velocity was about 30 mm/s. The bath flow entrained the top layer of the

metal and also flow reversal occurred in the metal pad. There was a horizontal plane of zero metal velocity

about 40 mm below the bath-metal interface. After 60 seconds the velocities in the bath and metal layers

were less than 5 mm/s and the motion of the bath-metal interface was almost completely damped (see

Figure 8 of [17]).

The maximum turbulent viscosity (Figure 9 of [17]) in the metal pad was 4.66x10-4 m2/s at 15 seconds and

was located below the center channel. This viscosity was 1447 times higher than the laminar viscosity of

molten metal at 3.22x10-7 m2/s.

Solution of the 8 continuous rectangular 100x200 mm ridges model

Apart from the shape of the cathode surface, most of the model dimensions were kept the same as those of

the “reference” flat cathode surface model. However, the metal pad was raised by 41.5 mm, in order to

maintain the same mass of metal considering the presence of the 8 continuous rectangular 100x200 mm

ridges.

The solution of this first irregular cathode surface model is presented in Figures 13 to 15 of [17]. Figure 15

of [17] shows the position of the bath-metal interface every 15 seconds. Figure 13 of [17] shows the

velocity field in the same front symmetry plane as Figure 7 of [17] also after 15 seconds. Due to the

presence of the cathode ridges, which acted like flow obstacles, the bath flow and especially the metal flow

were now quite different. The bath velocity was reduced in most bath regions and the metal pad had local

regions of high and low velocities near the cathode ridges. The horizontal plane of zero metal velocity was

raised towards the bath-metal interface by about 40 mm. This modified flow field could translate into

higher current efficiency.

The maximum turbulent viscosity (Figure 14 of [17]) was reduced to 3.85x10-4 m2/s and occupied a much

smaller area beneath the center channel. These results seem to suggest some stabilization of the bath-metal

interface.

Solution for the 8 continuous rectangular 160x125 mm ridges model

Since [17] was written, three new models testing different types of cathode surface irregularities were

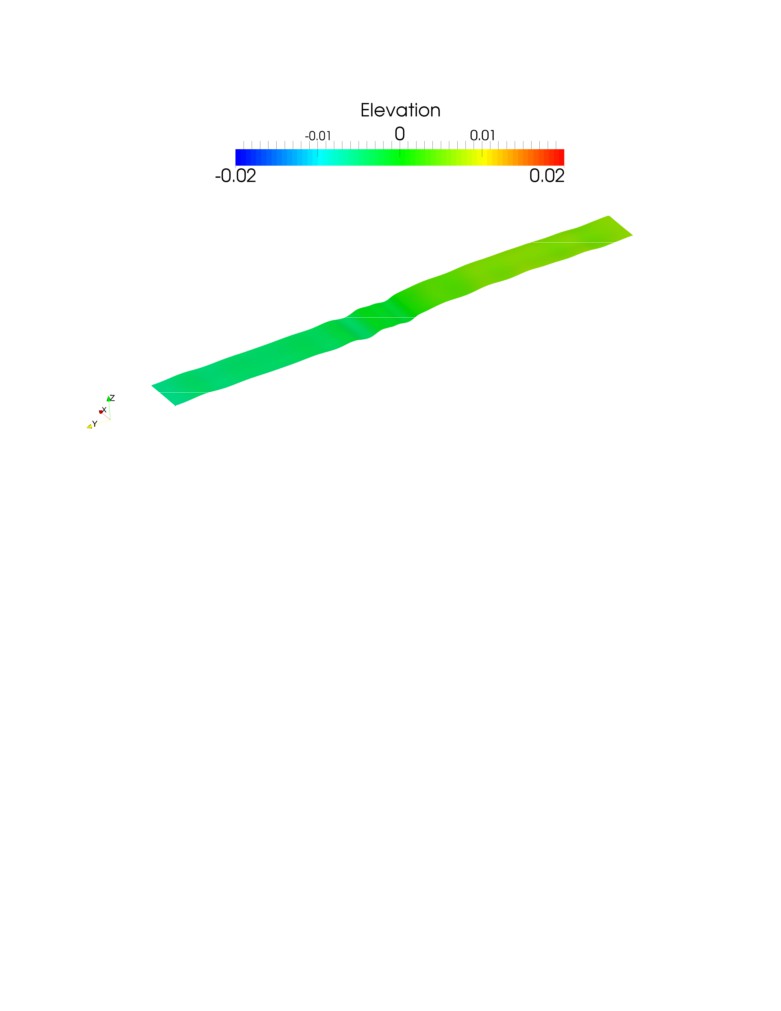

constructed and solved (see Figures 2 to 4). Figure 5 shows the position of the bath-metal interface for that

model at intervals of 10 seconds from 0 to 30 seconds for the model with 8 continuous rectangular 160x125

mm ridges. The interface is not significantly moving after that.

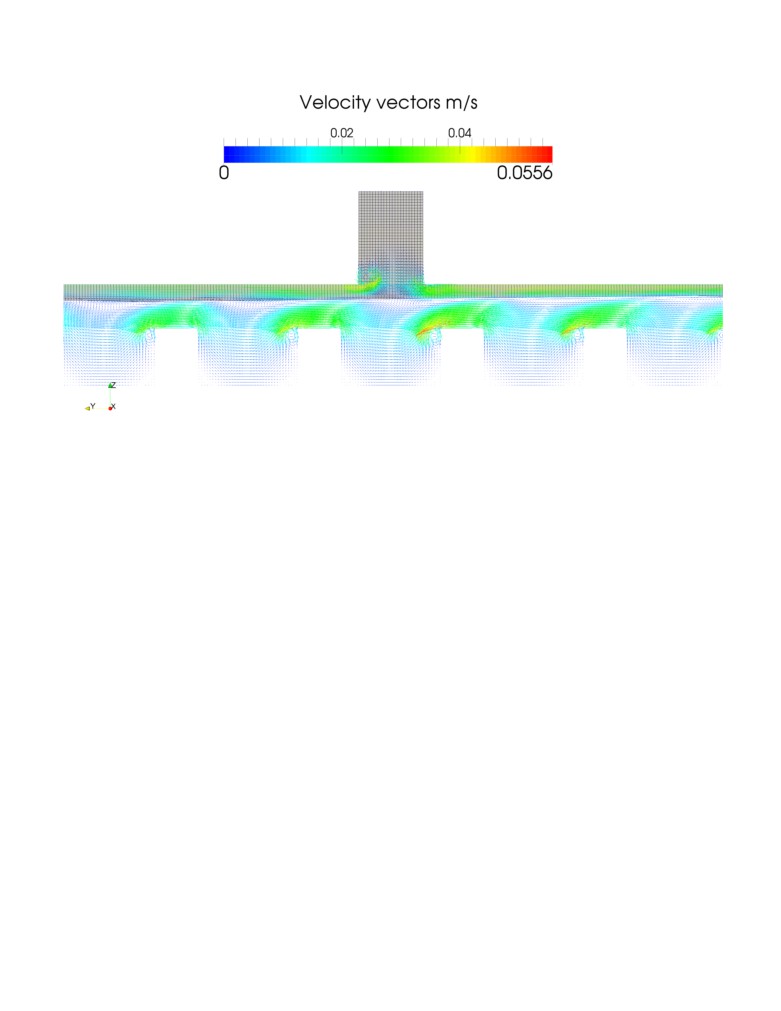

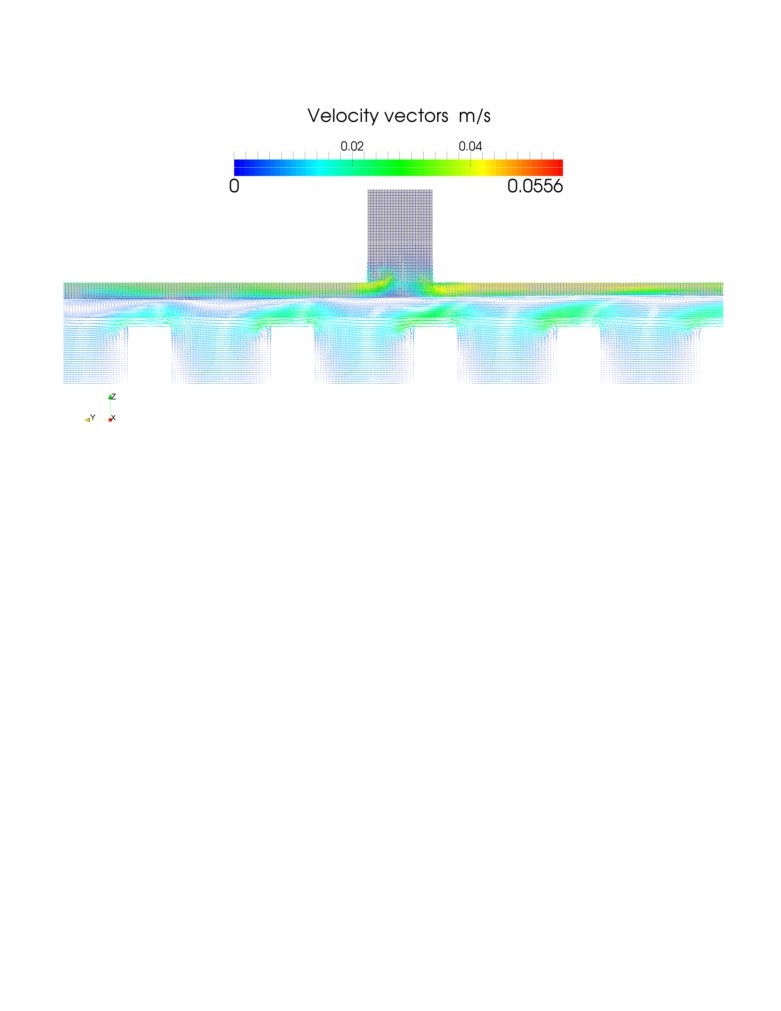

Figure 6 presents the velocity field in the front symmetry plane after 10 seconds for that same model. Due

to the presence of the much higher ridges, the maximum velocity is now located in the metal pad, and the

horizontal plane of flow reversal has essentially moved to the bath-metal interface. For that reason, this is

possibly an improvement over the previous model solution with 8 continuous rectangular 100x200 mm

ridges.

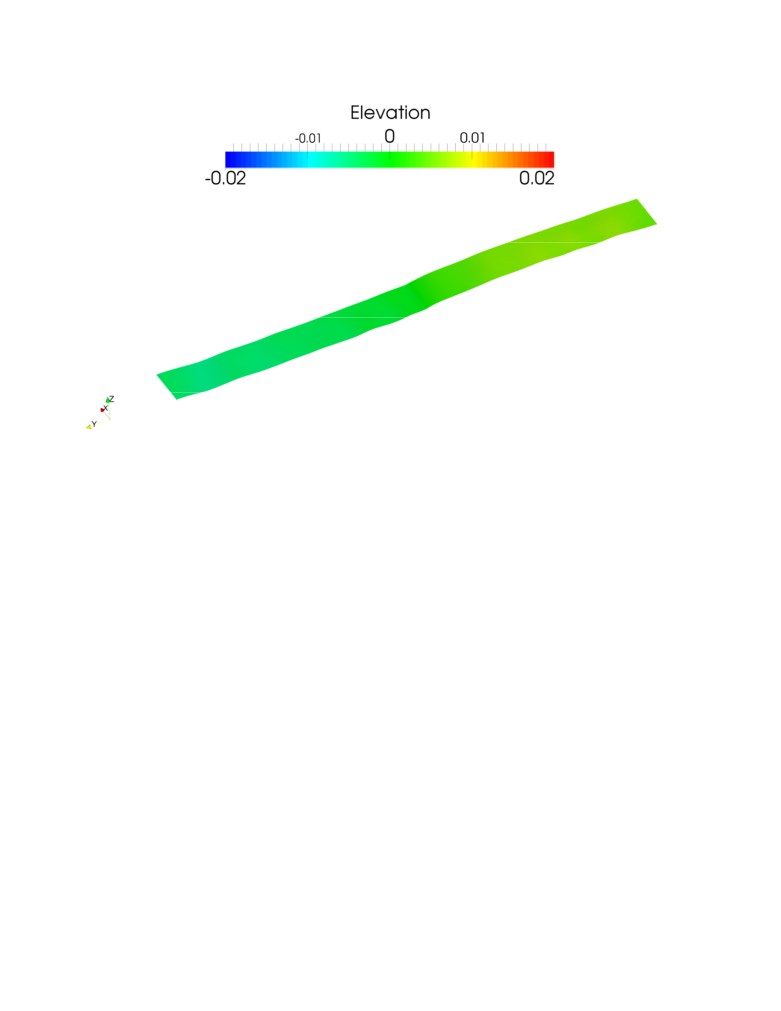

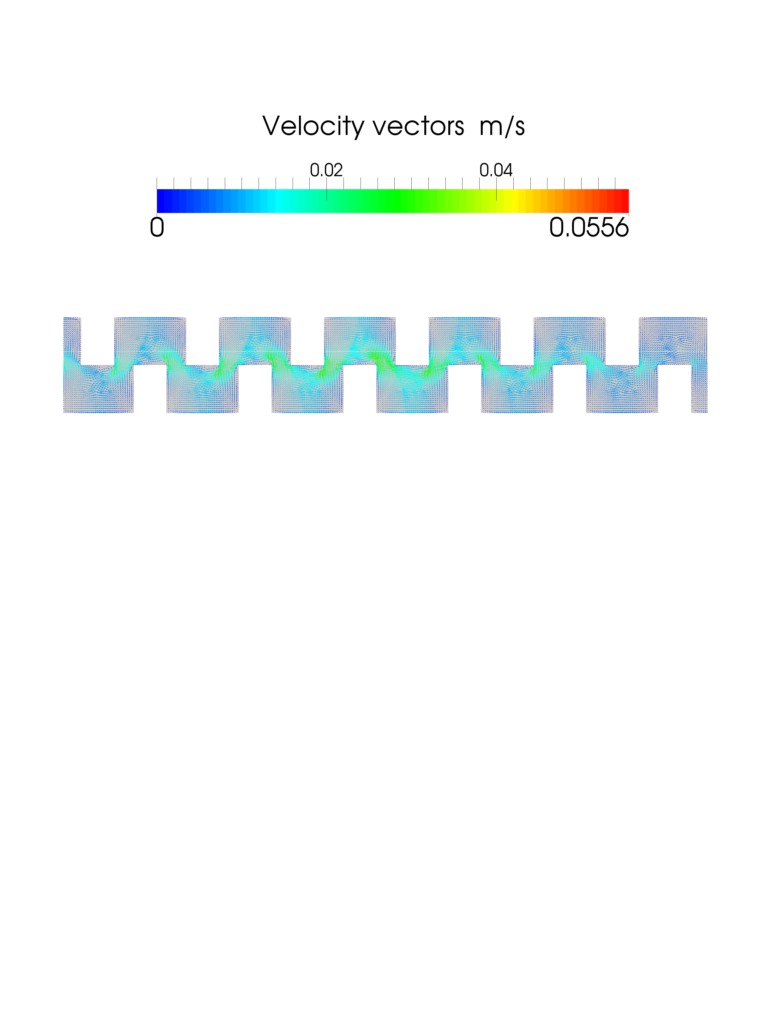

Solution for the 16 discontinuous alternating rectangular 160x125 mm ridges model

The next model wants to test if using discontinuous alternating ridges would constitute an improvement

over continuous ridges. Figure 7 shows the position of the bath-metal interface for that model after 10

seconds from the same starting point as all the previous cases. Figure 8 shows the metal pad velocity field

in a horizontal plane located 80 mm above bottom of the metal pad which is at the ridges mid height after

10 seconds. The metal flow is zigzagging around the discontinuous alternating ridges which might reduce

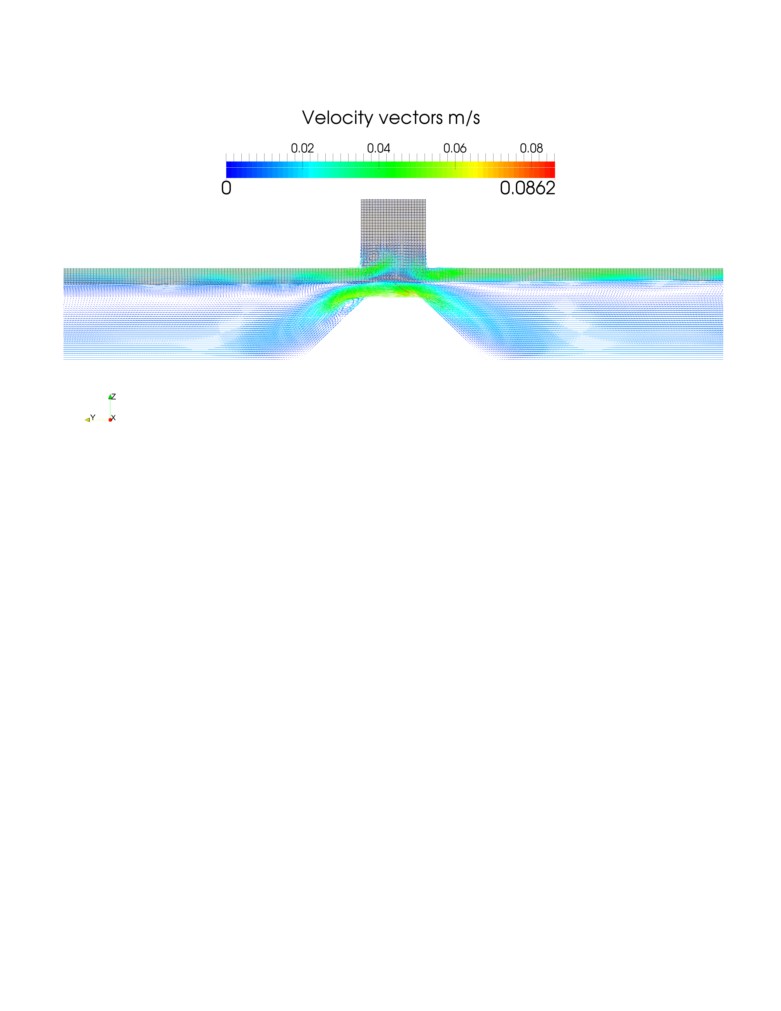

sludge formation. Figure 9 presents the velocity field in the front symmetry plane after 10 seconds for that

same model. The maximum velocity is located in the bath and the flow reversal move back down in the

metal pad.

Solution for the single trapezoidal continuous ridge model

The last model aims to test a quite different type of cathode surface obstacle to the metal pad flow inspired

from the recent Alcoa patent [20]. It is a single continuous longitudinal obstacle located under the center

channel. A trapezoidal shape was selected this time, the top section is almost as wide as the center channel

itself and there is only 4 cm of metal pad thickness left above it (see Figure 4).

Figure 10 shows the position of the bath-metal interface for that model after 10 seconds from the same

starting point as all the previous cases. Figure 11 presents the velocity field in the front symmetry plane

after 10 seconds for that same model. The maximum velocity is in the meal pad above the trapezoidal

ridge.

Comparison of the damping rate

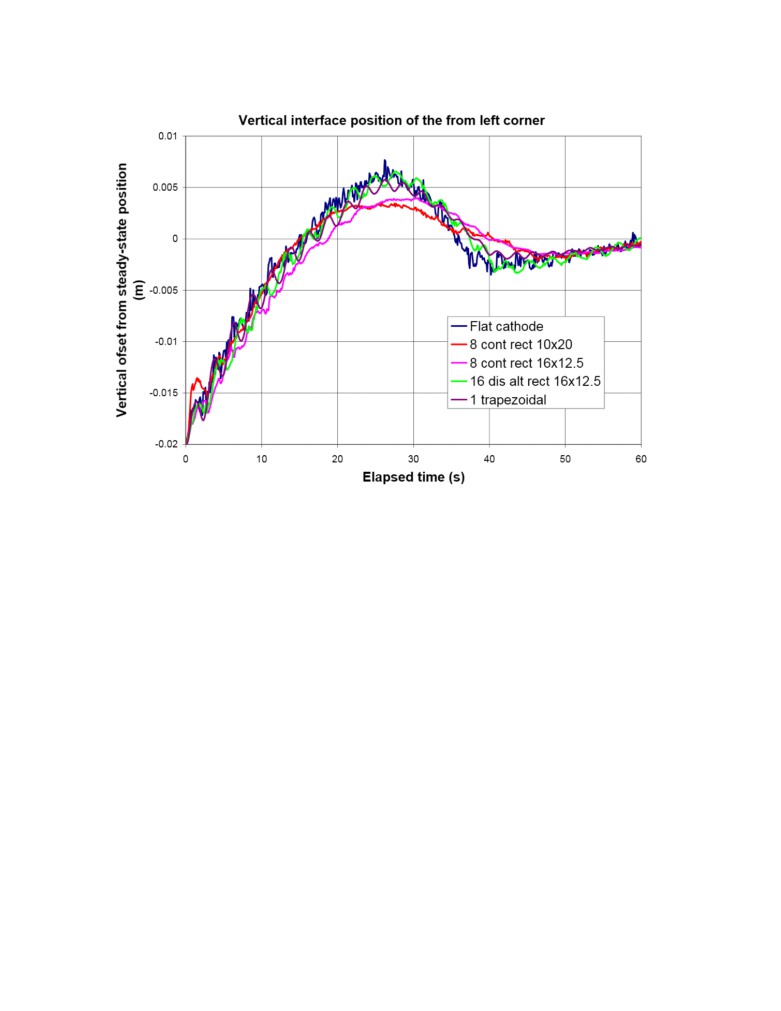

There was very little difference between the interface positions evolution for all the five cases modeled.

Only the intensity of the small ripples on the interface varies from case to case. The amplitude of those

small ripples increase when the top of continuous ridges get closer to the interface position.

The dynamic bath-metal interface position at the front left corner for all five models presented in Figure 12

was more revealing. There were clearly 2 families of curves. The evolution of corner position of the single

trapezoidal continuous ridge case and the 16 discontinuous alternating ridges case is very close to the

evolution of the

“reference” flat cathode surface case. For the two remaining cases, namely the

8

continuous rectangular ridges, there was less overshoot for the two oscillations at 26 and 45 seconds. There

were also less secondary ripples of the bath-metal interface for that second group. Yet, or all 5 cases, the

same interface positions were obtained at the same time after 50 seconds.

Clearly the presence of 8 continuous rectangular ridges had some effect on the bath-metal interface

dynamic evolution. It can also be argued that the 160x125 mm ridge size is very slightly more effective

than the 100x200 mm ridge size yet those higher and narrower ridges might erode faster.

Future work

The result of the

3D transient lateral slice model demonstrated that continuous longitudinal ridges

stabilized the bath-metal interface somewhat. Thus additional studies seem to be warranted:

a) Optimize the mesh size, time step, Courant Number, turbulence model, etc.

b) Further explore different dimensions of the rectangular ridge

c) Further explore other ridge shapes like triangular or semi-circular

d) Develop a 3D transient model of the entire reduction cell

The GY420 cell design has 48 anodes. Thus a 3D transient model of that entire cell would be about 50

times bigger than the present 3D transient lateral slice model. The bath and metal layers would be subjected

to time varying MHD Lorentz forces in addition of the constant gravity forces. Constant gas release drag

forces could also be added to the bath layer.

It has already been demonstrated that the OpenFOAM code can handle MHD flows successfully [21, 22]. It

is expected that a 3D transient OpenFOAM VOF formulation based cell model would be an excellent tool

for the analysis of cell stability especially to study the impact of irregular cathode surfaces. The computing

time on the same DELL Xeon ES-2697 V3 computer would be about 1500 CPU hours or about two

months. Clearly using an even faster computer with more than 28 cores would be required in order to

reduce the turn around time. Even nowadays, CPU resources are still too expensive to be able to carry out

such 3D transient cell stability analysis without a very significant R&D budget.

Conclusions

Lateral gravity waves were successfully simulated in a 3D transient slice model of a reduction cell. The

effect of the cathode surface on the bath-metal interface was investigated. The results showed that multiple

continuous longitudinal ridges promote some level of extra wave damping while other types of irregular

cathode surface irregularities have no observable impact.

The lateral slice model was solved using the VOF formulation in the OpenFOAM code on a DELL 28

cores Xeon ES-2697 V3 computer having 128 GB of RAM at its disposal. The calculation took about 30

CPU hours to calculate the transient evolution of the bath-metal interface during 60 seconds.

References

[1] N. X. Feng: Low Energy Consumption Aluminum Reduction Cell with Novel Cathode, China, ZL

200710010523.4, 2008.

[2] Q. Wang, B. Li, Z. He and N. Feng,

“Simulation of Magnetohydrodynamic Multiphase Flow

Phenomena and Interface Fluctuation in Aluminum Electrolytic Cell with Innovative Cathode”,

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B, Vol. 45B 2014, 272-294.

[3] M. Dupuis and V. Bojarevics, “Non-linear Stability Analysis of Cells Having Different Types of

Cathode Surface Geometry”, TMS Light Metals 2015, 821-826.

[4] M. Dupuis and V. Bojarevics, “Influence of the Cathode Surface Geometry on the Metal Pad Current

Density”, TMS Light Metals 2014, 479-484.

[5] M. Dupuis and V. Bojarevics, “Newest MHD-Valdis Cell Stability Studies”, Aluminium, 90 (2014) 1-

2, 42-44.

[6] V. Bojarevics, “MHD of Aluminium Cells with the Effect of Channels and Cathode Perturbation

Elements,” TMS Light Metals 2013, 609-614.

[7] N. Urata, “Wave Mode Coupling and Instability in the Internal Wave in the Aluminum Reduction

Cells”, TMS Light Metals 2005, 455-460.

[8] P. Davidson, “An Introduction to Magnetohydrodynamics”, Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics,

Cambridge University Press 2001, 363-386.

[9] H. Jasak, “OpenFOAM: Introduction, Capabilities and HPC Needs”, Cyprus Advanced HPC Workshop

Winter 2012.

[10] S. Hansch, D. Lucas, T. Hohne, E. Krepper and G. Montoya, “Comparative Simulations of Free

Surface Flows Using VOF-Methods and a New Approach for Multi-Scale Interfacial Structures”,

Proceedings of the ASME 2013 Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting.

[11] S. Y. Lee1, C. E. Park and V. H. Ransom, “On The Gravity Driven Force Terms of Single Pressure

One-Dimensional Multi-Fluid Flow Model in Horizontal Channel and Their Validation”, Proceedings of

ICAPP 2013 Jeju Island, Korea, April 14-18, 2013.

[12] D. R. Howell, B. Buhrow, T. Heath, C. McKenna, W. Hwang and M. F. Schatz, “Measurements of

Surface-wave Damping in a Container”, Physics of Fluids, Vol. 12, no 2, February 2000, 322-326.

[13] G. C. J. Morgan, “Application of the InterFoam VOF Code to Coastal Wave/Structure Interaction”,

Ph. D. thesis, University of Bath, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, September 2012.

[14] I. Lindmeier, C. Heschl, G. Clauss and U. Heck, “Prediction of the Flow Around 3D Obstacles Using

Open Source CFD-Software”, The Fifth International Symposium on Computational Wind Engineering

(CWE2010) Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA May 23-27, 2010.

[15] Ji-lin DING, Jie LI, Hong-liang ZHANG, Yu-jie XU, Shuai YANG and Ye-xiang LIU, “Comparison

of Structure and Physical Fields in 400 kA Aluminum Reduction Cells”, J. Cent. South Univ., (2014) 21,

4097−4103.

[17] M. Dupuis and M. Pagé, “Modeling Gravity Wave in 3D with OpenFOAM in an Aluminum

Reduction Cell with Regular and Irregular Cathode Surfaces”, TMS Light Metals 2016, to be published.

[19] F. R. Menter, “Review of the Shear-stress Transport Turbulence Model Experience from an Industrial

Perspective”, International Journal of Computational Fluid Dynamics, Vol. 23, No. 4, April-May 2009,

305-316.

[20] Y. Ruan and al., “Apparatus and Method for Improving Magneto-Hydrodynamics Stability and

Reducing Energy Consumption for Aluminum Reduction Cells”, US patent 2013/0032486 A1, 2013.

[21] A. Panchal, “Study of Liquid Metal MHD Flows Using OpenFOAM”, AE 494:BTP Stage 2, Dept. of

Aerospace Engineering, IIT Bombay.

[22] E. Mas de les Valls, “Development of a Simulation Tool for MHD Flows under Nuclear Fusion

Conditions”, Ph. D. thesis, Dept. of Physics and Nuclear Engineering Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya,

October 2011.

Authors

Dr. Marc Dupuis is a consultant specialized in the applications of mathematical modeling for the

aluminium industry since 1994, the year when he founded his own consulting company GeniSim Inc

(www.genisim.com). Before that, he graduated with a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Laval University

in Quebec City in 1984, and then worked 10 years as a research engineer for Alcan International. His main

research interests are the development of mathematical models of the Hall-Héroult cell dealing with the

thermo-electric, thermo-mechanic, electro-magnetic and hydrodynamic aspects of the problem. He was also

involved in the design of experimental high amperage cells and the retrofit of many existing cell

technologies.

Michaël Pagé is specialized in mechanical engineering in the field of numerical simulation. Graduated from

the University of Quebec at Chicoutimi in 2006, he has since worked in digital simulation for engineering

as well as product development firms. His professional experience and his personal interest in simulation

have enabled him to acquire a remarkable mastery of this technology. His technical versatility allowed him

to participate in several projects in the hydroelectric field in Quebec and abroad. Since 2013, he is one of

the leaders of Simu-K inc., a company that offers services in digital simulation. This new challenge allows

him to work with companies that are experts in their field to produce innovative solutions for their

customers.

Figure 1: Sketch of the GY420 cell design

Figure 2: Model geometries with 8 continuous longitudinal ridges 160 mm high and 125 mm wide

Figure 3: Model geometries with 16 discontinuous and alternated longitudinal ridges 160 mm high and 125

mm wide

Figure 4: Model geometries with a single trapezoidal continuous longitudinal ridge located under the center

channel

Figure 5: Position of the bath-metal interface every 10 seconds from 0 on top to 30 seconds on bottom for

the model with 8 continuous rectangular 160x125 mm ridges

Figure 6: Velocity field in the front symmetry plane after 10 seconds for the model with 8 continuous

rectangular 160x125 mm ridges

Figure 7: Position of the bath-metal interface after 10 seconds for the model with 16 discontinuous

alternating rectangular 160x125 mm ridges

Figure 8: Velocity field at the ridges mid height horizontal plane after 10 seconds for the model with 16

discontinuous alternating rectangular 160x125 mm ridges

Figure 9: Velocity field in the front symmetry plane after 10 seconds for the model with 16 discontinuous

alternating rectangular 160x125 mm ridges

Figure 10: Position of the bath-metal interface after 10 seconds for the model with a single continuous

trapezoidal ridge

Figure 11: Velocity field in the front symmetry plane after 10 seconds for the model with a single

continuous trapezoidal ridge

Figure 12: The dynamic bath-metal interface position at the front left corner for all five models